Equatorial Clash is not the kind of game I am usually drawn to. It’s a modern warfare game depicting events in the 1940s that uses NATO symbols for its units - usually I run from games like that. However, two items drew me to pick it up when I was placing an order with SNAFU games, SNAFU being an excellent online retailer in Spain and publisher of their own line of small to small-ish games. The first, and most striking thing, was the art design by Nils Johansson. Nils is definitely one of if not the most interesting graphic designers working in wargames at the moment and any time I see something he has worked on it will immediately draw a second (or third…or fourth) look from me. The other element was that this was about a conflict I had literally never heard of. Far from being the more conflict of the mid-20th century, this game is about the Peru-Ecuador border war of 1941. Given its amazing appearance and obscure topic, how could I not try it?

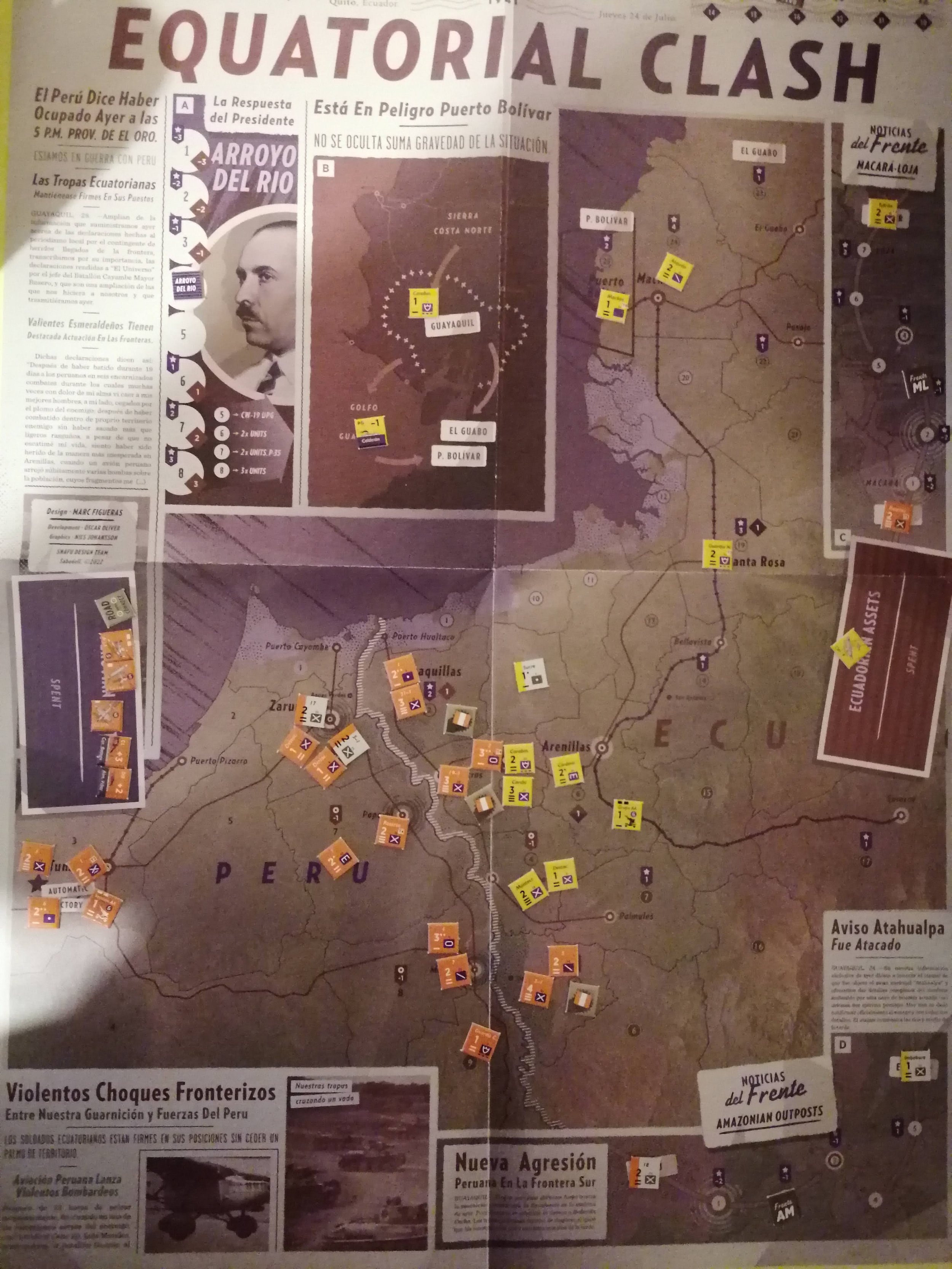

Initial game setup, Peruvian troops massing at the borders while Ecuador attempts to mobilise some opposition. Also, just look at this map, isn’t it great?

I wouldn’t describe Equatorial Clash as fiddly, but it is a game with quite a lot going on. Each round players will swap turns taking impulses where they select from a very wide menu of actions. You are restricted to only taking actions from one scale - e.g. Strategic, Operation, Tactical - but beyond that you can take as many as you want in a given impulse. This was my first time playing a game with any kind of system like this, so I can’t really comment on how like other games Equatorial Conflict is. I found it easy to keep track of the main actions I could do - types of movement, how to fight, that sort of thing - but was somewhat overwhelmed by the available choices beyond that. I focused on the basic actions for the first part of the game and only expanded to the more complex or niche as I learned the systems, which wasn’t bad for learning the game but was probably sub par tactically. There was also a lot of information for me to take on board when learning the game which caused me to overlook some of the rules - some quite significant, others less so.

Four turns in and Peru has breached the border in the south. They probably would have done this much quicker if I’d been better at reading the rules!

My biggest error was in misunderstanding how many Action Points each side has to play with in a given round. I understood rolling a d6 and adding any bonuses for areas on the map under that side’s control, I also remembered (after the first turn) how the politics track affects the Ecuadorian player. What I totally missed for the first half of the game was that the turn track also includes bonus APs for each side, so my early turns involved far fewer Action Points than they should have. While strategically disastrous for the Peruvians who struggled to get their offensive going, it did make the learning a little more manageable. A smaller pool of action points meant that I had a narrower band of actions to choose from and this did help me a bit in avoiding being totally overwhelmed by the menu of options and strategic possibilities present in the game. It also meant that I felt less foolish when I remembered some system I had forgotten, because I probably didn’t have enough spare APs to use it in the previous turn anyway. That said, when I discovered my mistake around turn 7 it nearly tripled the number of APs I had to play with and the game did become significantly more fun and interesting. So my advice would be to play the game correctly, revolutionary I know!

A little over halfway through the game and the Equadorian front is crumbling but Peru will need to penetrate much deeper to call this war a success. Huge amounts of Peruvian troops still haven’t been mobilised.

My other oversight was that you can take multiple actions in one impulse, so long as they are all at the same scale. Again I noticed my error a few turns in, around the time I found out I had far more APs to use than I thought. Initially I was moving all my counters one at a time. My realisation made the whole game make a lot more sense and to be fair, I had suspected I was doing something wrong but was too busy learning all the other systems to really be worried about it. The action selection is really interesting because it’s not like the game is played in strict phases - e.g. there isn’t a single movement phase where you do all your movement. You could choose to move all your counters one at a time, switching back to your opponent every move, or you can do all your moves in one big batch. The thing is that once you Pass that’s it for this round, so there is an incentive to spread your actions out but also you don’t want any of your units to be isolated or to give too much of the initiative to your opponent. It’s a small thing but it made for some interesting decisions.

Having finally figured out how the action points are allotted, the game has picked up the pace significantly. Both sides have assigned troops to fight in the other theaters and Ecuador is even attempting a counterattack along the border. Will it work? Doubtful, but it only has to stall Peru even more.

Equatorial Conflict isn’t necessarily a very complex game, and the rules do a good job of explaining it, but it is a game with a lot of moving parts and playing it solitaire meant that remembering all those parts was all on me. It is also strategically quite complex - I went for a fairly straightforward strategy of just pushing Peruvian troops over the border and taking the closest areas first, but I can easily see how the map and movement rules creates many strategic possibilities. You could get surprisingly deep into this game. This is partly why while I found it perfectly playable as a solitaire experience, I think it will be far better with another player who can help lighten the cognitive load and explore strategic possibilities that may never occur to me.

Peru handily secures the border region and has air dropped in paratroopers in the north in a bid to grab a high value region, but they have been pushed back to a less important part of the map. The war is going in the right direction, but a cease fire could be decided any turn now!

The part of Equatorial Conflict that impressed me the most was the depth of the combat. When reading the rules I was slightly confused about why there were so many kinds of units. Not being familiar with NATO symbols I had to learn them for this game (thankfully there is a breakdown of them on one of the player aids - as an aside the player aids are excellent) and my initial impression was that it felt a bit fiddly having all these unit types for what appeared to be a pretty simple combat system. However, as I played I found the subtle differences in unit strength and type emerged naturally through the gameplay and combat. For example, armour units have great offensive potential but are terrible at absorbing hits inflicted by your opponent and so really have to be supported by infantry. The differences in unit types didn’t need to be spelled out for me, I discovered them naturally through play. This may all be old hat to people who play more modern hex and counter games, but I was really impressed with it.

Cease fire is declared at the end of Turn 11. While Peru is easily pushing Ecuador back from their border it’s not enough to secure victory given their slow start which allowed Ecuador to accumulate VPs early.

One small thing I quite liked about combat was the CRT - specifically how generous it was at allocating hits to both sides in a combat. Going in to a fight with an overwhelming force is great and will likely give you a victory, but it is very unlikely you will escape unscathed. This attrition heavy CRT made each combat feel exciting and created some really interesting results. It avoids being overly random while still also difficult to predict the exact result. I was really impressed.

And on that note, let’s consider the map for a second. I don’t have a whole lot to say about it because I think it pretty much speaks for itself, but it is obviously absolutely gorgeous. The one thing I wasn’t totally clear about was the marking for Swamp and Mountain regions - I think I know which they are but I would have liked a sample in the rulebook because I am notoriously bad at colours. That’s the very slightest of complaints, and even if you ignore the game symbology the map itself makes it pretty clear where mountains and swamp are. Overall, I adore the fake newspaper aesthetic and the integration of the other theaters and tracks on the map is excellent. More games should look like this.

The map is the most immediately stunning part of the production, but the counters are nice and there’s lots of nice little detail in the map that it can be easy to miss when you’re distracted by the whole newspaper of it all.

I went in to Equatorial Conflict without brushing up on the history because I was curious how much of the history I could learn just by the game. It’s rare that I find a game about a topic that I know literally nothing about, so I was intrigued to try a blind play of it. I have to say that having read the background provided in the manual, the game does a pretty good job. Just based on the deployment of troops and victory conditions I could very clearly tell that Peru acted as the main aggressor, invading Ecuadorian territory with the game’s objective being a matter of taking as much territory as possible in the short duration of the war to justify the invasion. It’s hard going, though, and while the positions just across the border are pretty easy penetrating deeper into Ecuadorian territory is challenging. A design evoking the history without needing too much chrome or explanatory text is basically the ideal in my opinion and I think Equatorial Conflict does this excellently.

A side mat tracks VPs, action points remaining in that round, and the possible troops that Ecuador could mobilise if they change their political position - a constant reminder of what you could have!

I also quite liked the counterfactual that is baked into the rules around Ecuador’s president. The president of Ecuador had a poor relationship with the military and wasn’t interested in strengthening their position, in part due to fear of a potential military coup. This meant that Ecuador was very poorly equipped to meet the Peruvian invasion. Equatorial Conflict, however, lets you change this relationship and invest in the military rather than the president which could potentially unlock more units for you to use. Doing so could also prolong the war and will cost you victory points, so it’s a decision that must be heavily weighed. I expect it could also radically change your experience of the game. Ecuador is badly lacking in troops and a game where you take a path of resistance with your tiny forces would be very different from one where you shift the president’s position radically and suddenly have a much larger array of troops to play with.

Overall, I really liked Equatorial Clash. I don’t know that I’ll be playing it solitaire all that many more times, but it is definitely going into the rotation for whenever I can get an opponent who might be interested in it. It’s a fascinating game and if it’s an indication of the kind of designs coming out of SNAFU then I’m very interested in seeing what else they have planned!