I’m not sure how many times I’ve visited Gettysburg. Enough to have the entrance to the town’s Holiday Inn burned into my memory, as well as the layout of several family friendly restaurants. I can close my eyes and picture Little Round Top as if it was in my back yard. Growing up every summer my family would drive for 15 hours from central Virginia to upstate New York to spend a couple of weeks by a lake in the Adirondacks. When I was young, we didn’t drive those 15 hours in one go, instead we would stop over at Gettysburg for a night and then usually spend a second night somewhere far less remarkable near the New York border. My father is a huge American Civil War buff and I think he really enjoyed sharing that with us at Gettysburg – we mostly enjoyed climbing on cannons and on the rocks by Devil’s Den. Still, of all the many, many battlefields he took us to (most of them in Virginia) I always enjoyed Gettysburg the most. Maybe it was because we were on vacation, but I always preferred it over Chancellorsville.

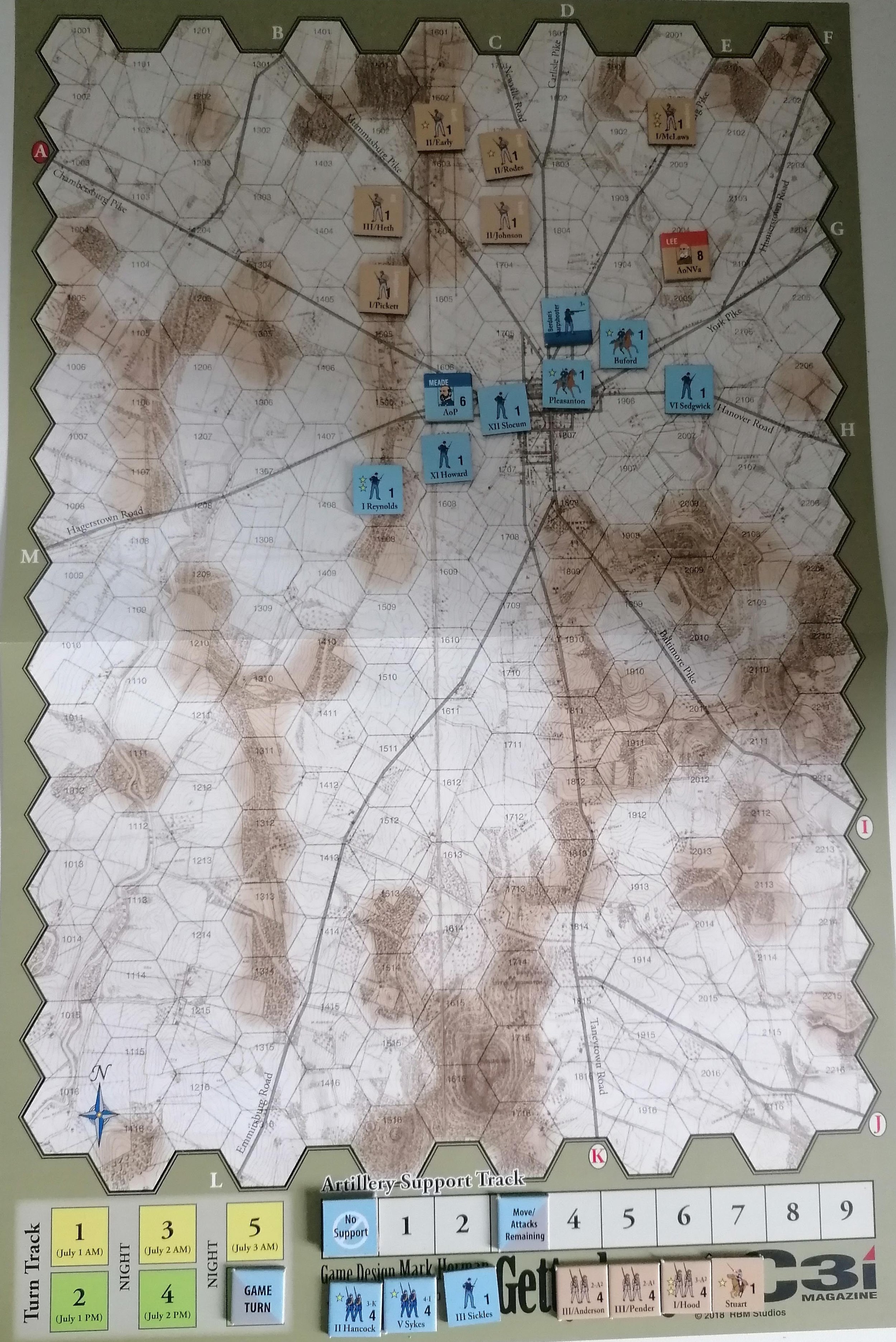

Buford’s cavalry spot the Confederate army and battle is joined. Most troops are off the board - two Union regiments enter at the southern edge of the board, but on the bottom left we can see the stacks of units that will be arriving in subsequent turns.

Not that I would have publicly declared that very often. I grew up in a very weird place when it comes to discussing the American Civil War. This history wasn’t dead and buried in Virginia – it was (and still is) hotly debated. Asking someone about their favourite Civil War battle was considered normal small talk and picking Gettysburg over Chancellorsville was considered suspect. You see, Chancellorsville was a great Confederate victory and, equally importantly, was in Virginia. Gettysburg was a great Union victory and, equally bad, was in the North. My father grew up in Washington, DC so I was spared some of the more hard-line Neo-Confederacy that lurked in local discussions of Civil War history, but he had still been raised on popular history that was steeped in the Lost Cause (a major historiographical movement that deliberately tried to rehabilitate the South and deny the war’s real causes and horrors).

On Turn 2 the battle is joined. One Confederate regiment manages to make it into Gettysburg but is quickly encircled, meanwhile the other regiments will battle for control of the high ground further west.

Combat goes the Union’s way - no Confederate regiments are eliminated but on the west they are forced to retreat and in Gettysburg the Regiment is blown and will have to return on the next day.

This is all a preface to explain why I have a very strong interest in the American Civil War, but I also have a lot of reservations about how it is handled, particularly in popular culture and wargaming. Despite my interest in the conflict, I have been slow to pick up ACW games. However, when I decided to take a plunge and buy my first copy of C3i to explore my newfound fascination with wargame magazines (something I somehow hadn’t known about before), I decided to pick the one with Mark Herman’s Gettysburg.

The Confederate attack on Turn 3 pushes the Union back toward Gettysburg, they take up positions on the nearby hills. The Sharpshooters are isolated, but as a guerilla unit they will reform closer to the Union lines next turn.

I’ve rambled on long enough already, so let’s get right to the point: I really liked this game. I played it solitaire, which wasn’t ideal because it meant I missed out on some of the fun of the blind bidding rules for artillery support, but overall, I think it works just fine as a solitaire experience. Some people have even come up with rules for automating artillery, which I looked into, but they seemed more complicated than I wanted out of a first play.

Turn 4 is when things are going to start getting bloody. This is the positioning before the shooting starts, the Union has the high ground but will it be enough?

I’ve come to realise that I really love games with interesting movement and positioning to play with. Lots of dynamic movement does a lot for me, and that is something that Gettysburg offers in spades. There is no strict limit on how many moves either player can take during the Movement Phase, but as each unit enters the enemy’s Zone of Control they slowly get locked down and can’t move anymore. So, you have this dwindling number of movement opportunities. There’s a real push and pull around when to lock down an enemy unit while securing the most advantageous position for yourself. I also really appreciate the random element where when one player passes the other player rolls a d6 to determine their remaining moves. It’s a welcome bit of unpredictability that can encourage an early pass because your opponent may end up with insufficient moves to complete their plan – but at the same time they could roll high and it could all be for naught.

The Confederates managed to get a toe hold on the ridge near Gettysburg but at great cost - large numbers of troops are blown and won’t be back until the final turn and Confederate artillery is running out!

What really makes the movement element sing, in my opinion anyway, is how it’s completely divorced from the attacking. The movement phase is resolved in its entirety before you move on to resolving attacks. Back when I played miniature wargames games with this kind of division weren’t really to my taste, but in Gettysburg it really works. It means that the movement phase never slowed down so I could resolve attacks. Then, during the attack phase, it makes the retreats feel impactful because that player can’t just take another action to move forward one hex and attack again. I was able to fully focus on just the decisions of each respective phase as I played them. Sure, I had to plan for the next phase in the current one, but that phase never interrupted the fun I was having now. It never felt like the game had to slow down while I resolved something or made a series of boring plays because they were strategically optimal – I was fully engaged with the experience the whole way through.

Opening of the final turn. The Confederate’s have brought back on their blown regiments and both sides are out of artillery, but the Confederates are currently losing with 3 lost regiments to just 2 eliminated Union ones. Can they pull out an unlikely victory?

Gettysburg is a very light game, in wargaming terms anyway. There aren’t a lot of counters, combat is a dice off with only a few modifiers, but it does a lot with a little. I wasn’t buried in the rulebook while playing it and I still felt like I was playing Gettysburg. Now, it doesn’t exactly capture every moment of the battle – if you’re looking for a detailed simulation that will return historic results this probably isn’t the game – but I think it strikes a good balance between evoking the history of the battle and being an enjoyable game that is fun to play. I had a lot of fun with Gettysburg and I’m looking forward to coaxing someone into playing it with me sometime in the future.

The Confederacy’s final attack has been defeated, the Union controls Gettysburg and has suffered fewer casualties, winning the day if not the war (yet).