Few medieval figures have captured peoples’ imagination quite as much as Al-Nasir Salah al-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, more widely known in the western world as Saladin. His successful military campaigns in the mid and late twelfth century, along with his reputation for charity and mercy toward defeated foes, have inspired much discussion and debate ever since his death. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that his famous battles against the Crusader States and the Third Crusade have inspired quite a few wargames, including several battles in GMT Games’ Infidel, which I wrote about previously. The latest addition to the canon of games about the sultan and his military career is Saladin from French publisher Shakos Games.

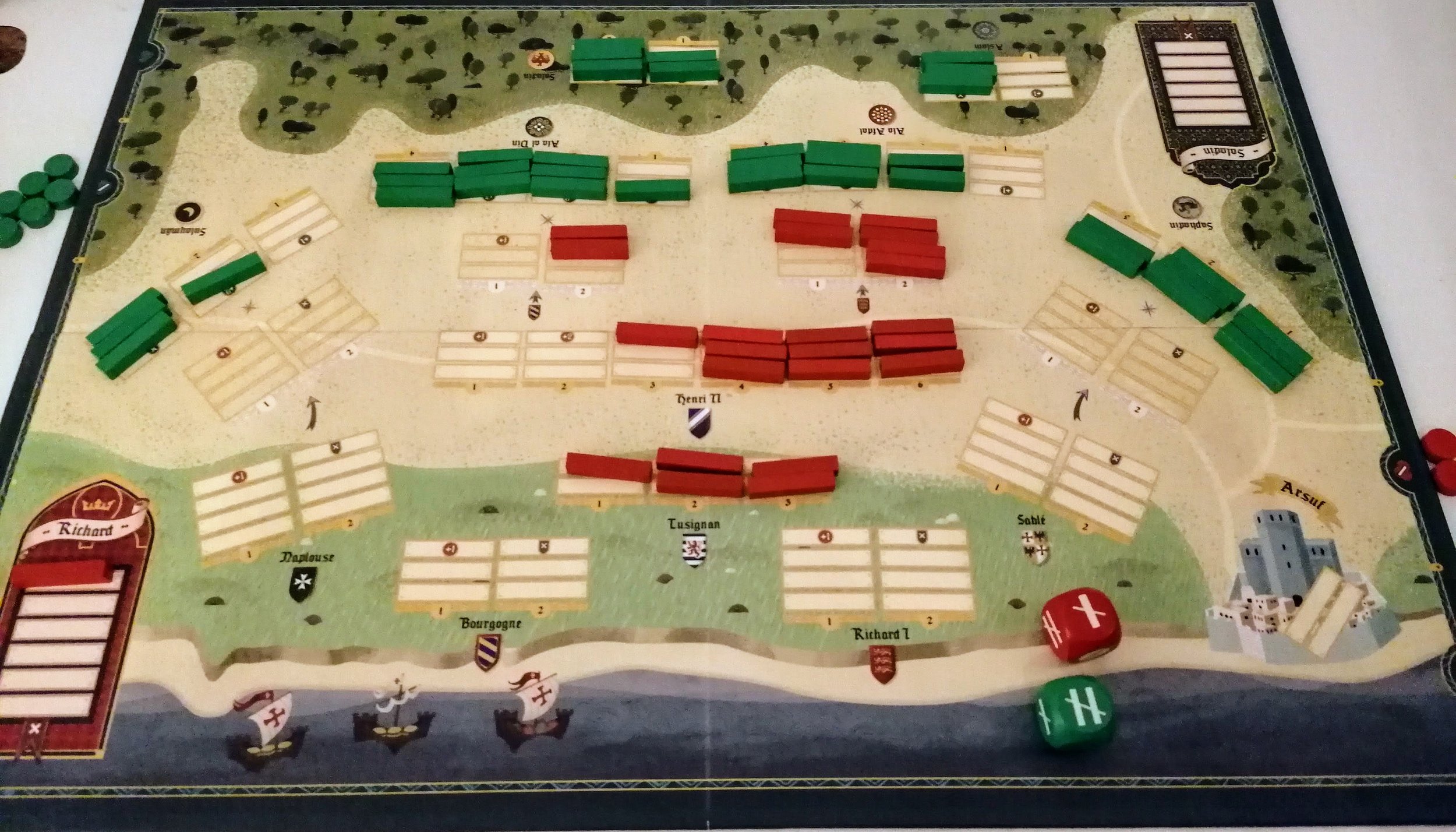

Opening set up for my first solitaire game of Saladin. The board is gorgeous but with questionable colour choice for people with colour blindness.

Saladin is the first entry in Shakos Games’ En Ordre de Bataille series, which I believe will be a collection of smaller games that depict famous battles from history. Saladin includes two battles in the box – Hattin and Arsuf – one on each side of the board. While I was more interested in trying Hattin, a battle that seems weirdly unpopular in historical wargaming despite its importance to history, the rulebook was very explicit that I should play Arsuf first to learn the system, so that’s the one I played. I initially set it up to play with a friend, and we successfully completed the first round of the game before our respective parenting responsibilities intervened and we had to take a rain check for the rest of the game. I set up Arsuf again a few days later and played it solitaire this time. The game has no hidden information, so it plays reasonably well solitaire, but I did feel like I was missing out on some of the experience without a human opponent.

The opening of the game did not get off to a great start for the Crusaders. Two successful charges were launched, but they have suffered significant casualties as a result.

The core of the system is that each player has a pool of order tokens and a selection of cards representing each of their commanders at that particular battle. Each card has a list of actions that it can take which each cost a particular number of order tokens to use. When you choose an action on your turn you flip that card over to its Activated side. Most cards have a smaller pool of actions they can still take once Activated should you wish to spend more order tokens on them – but you must activate all your commanders in a round and each card as a zero-cost action that is very bad, so you have to conserve your orders to make sure you can activate everyone. The other main feature is that available actions depend upon the commander’s status. Commanders (and their units) can be Committed, i.e., in melee, or Uncommitted, i.e., waiting to charge. Generally, the way a commander becomes Committed is by using the Charge action (either via the good Charge action or the not good Reckless Charge action), but the Ayyubid units have Reaction abilities that can cancel a charge action while still causing the Orders to be spent so the Crusaders have to be tactical about waiting for the right time to charge.

Bourgogne and Richard I return to their starting position to hopefully charge again. Unfortunately the entire left flank has been wiped out and the desperate charge on the right could be going better. They have at least successfully driven the Ayyubids from Arsuf.

This mechanism of Committed vs. Uncommitted and having the Crusaders time their charges, then withdraw, then charge again feels much more suited to the Battle of Hattin than it does to Arsuf. As a model of Arsuf there is very little to represent how Richard I’s goal was initially to march through the battle zone and not fight. It was only when the Hospitaller rear guard got sick of the constant harrying from the Ayyubid archers and charged that Richard was forced to commit the rest of his army to the fight. I couldn’t help but think of my experience with the Arsuf scenario in Infidel (which you can read about here: https://www.stuartellisgorman.com/blog/first-impressions-infidel-arsuf-1191). While Infidel is a very different system, and not exactly a perfect model of Arsuf itself, that did a much better job at capturing the dynamics of Arsuf by representing the fighting march tactics of the Crusader army on that campaign and the distinct goals of the two armies. The version of Arsuf in Saladin did feel like a crusader battle, if one that leans a bit too heavily on Muslim light horse archers without also including the heavier melee troops that were also a core part of warfare at the time, but it did not feel particularly evocative of Arsuf to me. The reason I think the system may suite Hattin better is that battle did see multiple charges by desperate crusaders, who would then rally and charge again, failing to break the Muslim line each time. The Committed/Uncommitted system feels better suited to that battle than to Arsuf which didn’t see nearly as many repeated charges.

Both Crusader flanks collapse and the core is suffering under a barrage of arrows. Richard and Bourgone have successfully charged again but are making barely a dent in the Ayyubid lines.

There are several aspects of Saladin that I really like. The fact that all the actions that involve melee fighting involve rolling both player’s dice, and thus risk inflicting injuries on both sides, is great. It’s a very simple way of capturing how even if you launched your big charge, you’re going to take losses. I also like the dice themselves – the distribution of no hits, one hit, two hits, and a loss of command point really work for me. The committed/uncommitted status is also interesting, although I’m not in love with the fact that the available actions when committed are kind of boring. As the Christian player it kind of forces you to pull back your troops and try to charge again, which doesn’t really feel very realistic to warfare at the time, and I found a little frustrating as a game mechanic. I like the fact that each unit has a clear specific commander that I can complain about when my dice come up blank after ordering them to assault Arsuf yet again, Guy! The game itself is fun to play, it has interesting decisions to make, and the dice chucking is fun. It’s also gorgeous, but hopefully the pictures are conveying that sufficiently – although I would note that it is not colourblind friendly, which is a shame. There isn’t really an excuse for making a game inaccessible like that.

Crusader defeat! The casualties were quite one sided in the end as the Crusaders just were not able to deliver a crushing blow to the Ayyubid lines.

Where the decisions get really interesting is in the mid to late game. Each round after the first you have to discard a number of orders back into the game box – so while you start with plenty of choices and can ignore the terrible zero cost actions in the early game, as the game progresses you have to prioritise certain units and take bad actions with others. This to me is the most interesting aspect of the game – deciding what to prioritise with a limited action budget. That said, it’s also where I think the game’s biggest flaw sits: its victory condition.

You win a battle in Saladin by being the last player with order tokens left. The easiest way to take order tokens from your opponent is by killing units - every six units costs them an order - and by completely wiping out a commander, which will cost them one extra order at the start of each round. Since having few orders makes it harder to fight back, Saladin seems like a game that could have a situation where it is clear the game is over a few rounds before victory is actually achieved. Now, games in Saladin aren’t very long, so it’s not like you’re going to be slogging through hours of unwinnable game, but even playing 10 minutes of game where you can’t win isn’t a great experience.

I also just don’t find this victory condition very inspiring. What does it really represent? I get that diminishing order pools as the game progresses represents loss of command, diminishing options, and general fatigue at the battle as it drags on, but what does no orders mean? I would have significantly preferred a more dynamic and possibly asymmetrical set of victory conditions that weren’t quite so attrition focused on top of the constant drain on orders affecting both sides’ ability to meet those goals. That said, I still have only played Saladin one and a bit times, and I haven’t tried the Hattin scenario at all, so it is far too soon for me to pass judgement on it. For the moment, I like the system, but I’m not entirely convinced that every aspect of its application here works. I’m going to play it some more, though, and we’ll see how that changes things!

Recommended Reading:

Saladin by Anne-Marie Eddé

The Life and Legend of Sultan Saladin by Jonathan Phillips

The Crusades by Thomas Asbridge

The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades by Paul M. Cobb