I’m low-key obsessed with block games - there’s something that’s just so appealing to me about pushing blocks around. Maybe it’s somehow related to all those years I spent playing miniatures wargames. Block games also tend to be operational scale and card driven which are two things I really like, plus they’re usually relatively simple and easy to play. All of those are positives, but I think there’s something about the tactile nature of the blocks and the simple fog of war that just really works for me. While I have very much enjoyed my time with the Columbia block games I have played, I am also always on the lookout for new and interesting takes on things I enjoy. This meant I was immediately intrigued when I first saw the Conqueror’s Series from Shakos Games. These games, all about Napoleon so far, promised a familiar yet distinct variation on the block games I was used to. However, I held off on buying one for the simple reason that I have had to impose a limit on myself on the number of unplayed block games that I own. The issue is that while I love block games, they are not very solitaire friendly and they also lose a lot of their appeal when you play online. Since I have very limited face to face gaming time this means that I don’t play as many block games as I would like. I got lucky, though, and Napoleon 1806, the first game in the Conqueror’s series, was picked to be the game of the month for November by the Homo Ludens discord and so I made sure to carve out some time to play it.

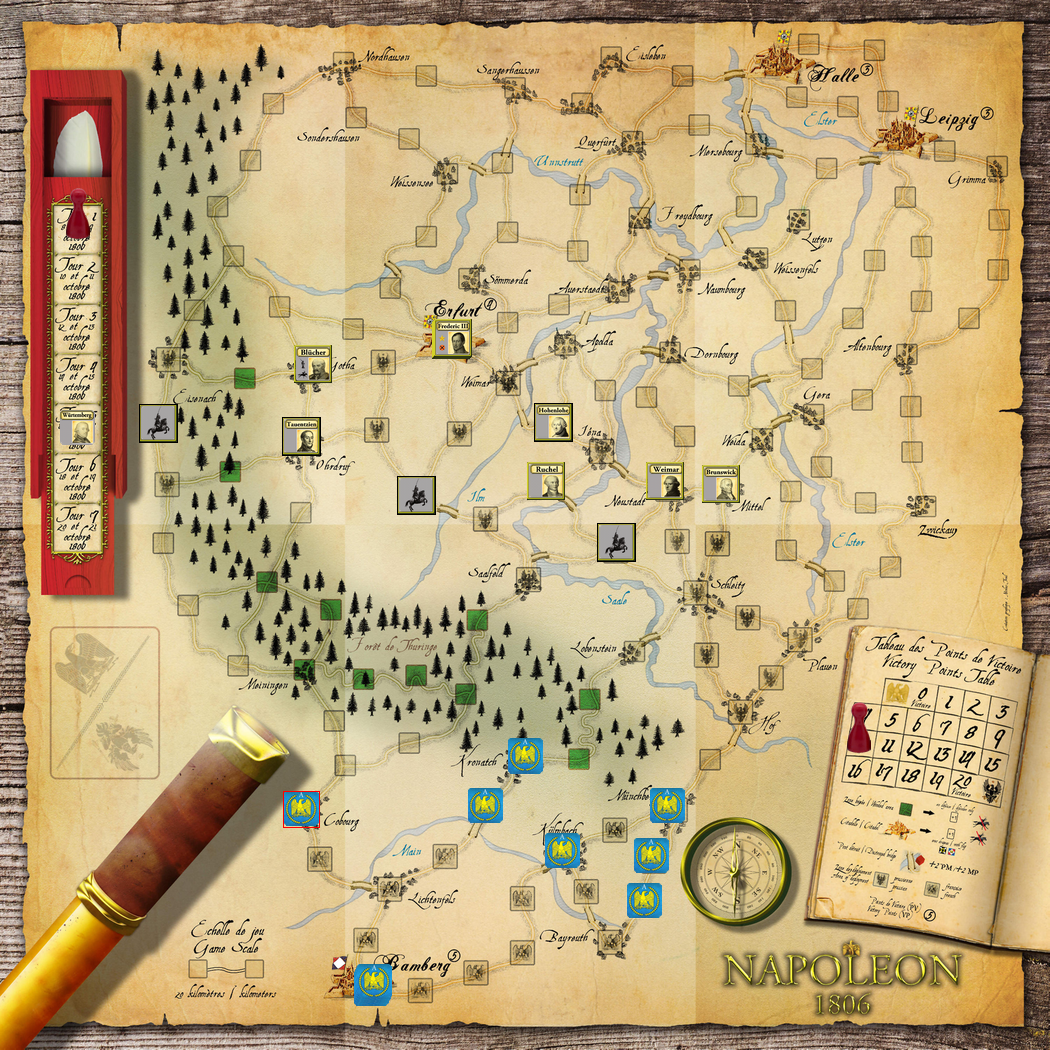

Initial set up for Game 2. I’m the Prussians this time since I had one game under my belt and it was my opponent’s first. The black horse and rider blocks are “dummies” that are immediately eliminated if they contact an enemy block. I need to survive seven rounds to win - or get to 20 VPs but that’s not going to happen. If Napoleon can drag the VPs down to 0 he wins.

Unfortunately, while I was able to play two games of Napoleon 1806 last month neither one of them was in person. While the Vassal module for Napoleon 1806 is pretty good and I had a relatively easy time using it, playing block games on Vassal or Tabletop Simulator always leaves something to be desired - Rally The Troops is better but has a more limited selection. That tactile nature of pushing the blocks around is so satisfying and I miss it every time. There are also elements of the interface that would be easier in person but are rendered clunky online. For example, Napoleon 1806 has a separate board for tracking unit strength and frequently has you flipping cards from the top of your deck to determine a number of effects. Both of these would be easy to manage in person, but as your unit board, the main board, and the card decks are all in separate menus on Vassal this can make for a mildly tedious play experience. That all said, being able to actually play these games, no matter the slightly clunky interface, is vastly preferable to not getting to play them at all. I do wish all digital block implementations were as good as those on Rally the Troops though.

End of Turn 1. I’m attempting a threatening flank on the left and bluffing in the middle while Napoleon makes a big push on the right. I gain a VP each turn that I control three of the citadels and Napoleon will gain a chunk of VPs if he can take Erfurt, Leipzig, or Halle from me so I need to protect him. The red cube is a bridge I’ve elected to destroy, increasing the cost of moving that way substantially.

Napoleon 1806 makes some really interesting tweaks to the classic Columbia block game format that I’m used to. I think the two most interesting are how it handles unit strength and movement. There are other interesting minor differences but the only one that I found myself routinely reminding people of in my two games was that blocks from both sides can cohabitate in a space, there is no mandatory combat when both sides arrive at the same location. This makes for some interesting decisions as you suffer a combat penalty if you fight on the same turn you move, but if you don’t initiate combat your opponent could simply walk away on their turn. However, it’s really how the system overall handles movement and combat in general that is what really sets these games apart in my mind.

End of Turn 2 - I continue by bluff in the centre and push a bit further on the left, also bluffing some. Napoleon pushes up the right but I’ve managed to get a block into Leipzig so I’m feeling a little safe on that front. My goal is mostly to delay him. Thankfully this past turn we also had the Rain event, so that slowed the Napoleonic advance.

First, let’s talk about movement. In Napoleon 1806 on your turn you can choose to activate a number of “Corps”, the term for blocks that represent armies as opposed to the blocks that represent leaders, in one location. Once you have chosen how many you wish to activate, you flip the top card of your deck (each player has their own unique decks) and you use the value in the top right corner as your Movement Points for that turn. A number of potential elements can add or subtract from this number. Some commanders and Corps have abilities that increase movement, some events decrease movement, and for every Corps after the first that you chose to activate you suffer minus one movement point. This can mean that in certain conditions, such as activating multiple Corps on a turn when the Rain event has triggered, you may not be able to move at all. Not knowing how far you can move in a turn makes it challenging to plan your strategy but does reflect the difficulties that commanders at the time would have had moving these large armies across sometimes difficult terrain. The games somewhat subtle asymmetry also appears here as the Prussian side has a deck with much lower values than the French, meaning that in general they are not able to move nearly as far.

End of Turn 3. We had our first fight on the left which revealed that Napoleon himself was there! Things went very badly for the lone Prussian commander who is also now entirely devoid of meaningful support. Meanwhile my bluffs are slowly crumbling but are at least distracting Napoleon’s Corps some. Napoleon has also repaired the broken bridge and is splitting his forces between Erfurt and Leipzig.

Napoleon 1806’s other significant feature, and the one that attracted me the most, is how it handles block strength. Instead of strength being printed on the blocks, there is a separate board for each side that includes a line for each Corps. The strength of your Corps is tracked on this board but a player screen hides it from your opponent. Each Corps has two key stats to track: strength and fatigue. Strength is represented by cubes with the number of cubes each Corps has determining how many cards it can contribute to a combat. This is tracked in thresholds, i.e. if you have five or more cubes you draw two cards for combat, four or less and you only draw one. Each cube is also worth a victory point for your opponent if it is eliminated.

End of Turn 4. Left and centre positions have crumbled and Napoleon is at the gates of Erfurt. However, the VP position could be worse and we’re now more than halfway through the game. I just need to hold out for three more turns, and I’m about to get some reinforcements in the north!

Fatigue is represented by cylinders that are added to the the Corps on a track just beneath the strength track. Fatigue can be gained by marching more than three spaces in a given turn, arriving at or leaving a space with an enemy block, a number of event cards, or as a combat result. Having more than five fatigue costs you one card in combat and will cause the Corps to suffer a casualty at the end of a round and having eight fatigue triggers the immediate elimination of the Corps regardless of strength remaining. Managing your fatigue levels is essential to good play in Napoleon 1806.

On Turn 5 the French launch a major assault on Erfurt. Due to the rain Napoleon III was unable to reach the city in time to provide support. However, some truly stunning card draws on the part of the Prussians saw both sides suffer heavy fatigue but ultimately resulted in a stalemate so both sides continued to contest the space.

One final mechanism to note since I’ve hinted at it a few times already: combat resolution. Like with movement, combat is resolved by flipping the top card(s) of your deck but instead of the number in the upper right you are using symbols in the bottom left. Orange symbols inflict fatigue, symbols of your opponent’s unit colour inflict casualties. The number of cards drawn is based on the Corps present and their strength, plus event cards played from your hand and/or commander abilities. Once again the decks are asymmetrical, so the French have consistently better combat results than the Prussians.

The state of the Prussian forces at this stage in the game. The grey cubes are infantry, purple are cavalry, and orange cylinders are fatigue. We’ve taken some serious abuse but we’re still holding strong!

I will say that I don’t think the Napoleon 1806 rulebook does a great job at explaining all of these differences to you. I am reliably informed that this is primarily a problem with the English translation of the rules, and that the French original is much better. I will say that I played my first game pretty incorrectly and would have really appreciated a more detailed breakdown of what the Operations Phase of the game entailed. There are great examples explaining the Draw Phase and things like Combat but I found the Operations Phase, which is the bulk of the game as it is when you’ll be activating Corps and moving them around, could have benefited from greater clarity.

In my first game we managed to completely misunderstand how movement worked and played it like a traditional CDG block game - playing cards from our hand for their number values to move Corps around. This made for a very quick game as we were only activating about three Corps each turn, leaving most of the units largely unused. This was obviously the incorrect way to play and with some help from a French speaking player I managed to correct these errors, but I will say that to some degree I preferred this mistake.

The start of Turn 6 - Erfurt remains contested but Napoleon is approaching from the left. Can Napoleon III reinforce the city in time? Should he? On the top right, the French have arrived at Leipzig but elected not to fight until they can bring in more reinforcements for a general assault.

I don’t know that I particularly like the system of flipping your top card to see how far you move - or maybe instead what I don’t really like is how you can activate every Corps every turn. There are incentives to not activate them all, if you don’t activate a Corps it recovers all its Fatigue at the end of the turn, but I did find the game took a little long for my taste with every unit activating ever turn in my second game. This was particularly exacerbated by the fact that in my second game I played the Prussians who just need to survive the game’s seven rounds to secure a victory. This meant that I would do a little movement, set up some defensive positions, and then sit as the Napoleon player activated the rest of their enormous army. I felt like I played around 30% less of the game than my opponent did. I expect that at a higher level of play the Prussian player probably does more, but I also don’t know that I enjoyed the experience enough to play it enough times to get to that level. It all just felt a little too long for my taste. That’s not to say that Napoleon 1806 was a very long game, certainly not on the scale of other wargames, but my free time is limited and it just felt long for what it was.

Middle of turn 6: another big battle in Erfurt, this time featuring l’Empereur himself. However, some stunning draws meant that the Prussians inflict one more casualty on the French than they receive, driving the French from Erfurt even as one Prussian Corps is eliminated by fatigue and the rest severely crippled. Frederick III’s decision to reinforce the city is validated!

What I did really like about Napoleon 1806 was the combat and the ways of tracking battle damage. The fatigue system in particular is amazing and the fact that you can’t see just how badly beat up your opponent’s Corps are makes for some really tense game moments. I had times in my second game where I was convinced that my opponent was going to march in and obliterate a few Corps that I had which had been badly mauled in two previous fights. However, my opponent’s Corps were so badly fatigued that he couldn’t really afford to push them forward to attack, or if he did they were so penalised that they had barely any impact. Two armies that in a previous round had been drawing 7 and 9 cards respectively, two turns later were drunkenly punching each other with 2 and 3 cards. It elegantly represents how these armies would get run down, not only in terms of men wounded or killed but also just the bone tiredness that would set in after days of constant campaigning. I love these systems.

Start of the final turn and things are looking pretty good for the Prussians. That said, the Corps in Erfurt are in very poor shape and if Napoleon can eliminate them and seize the city he can still win! Alternatively, if he can drive them out and get lucky in Leipzig he could potentially secure a victory.

I should also briefly mention the two ways that the game can be played. In my first game we used the standard rules where the blocks are placed face up on the map and deployment of them is strictly defined by their historical positions. This allows you to see what Corps is where but you still can’t know the exact strength of any of them. In our second game, at the insistence of our French observer, we played using the “Grognard” rules which switch the game to a more classic hidden block set up, where your blocks are only visible to you and your opponent just sees a generic back. It also introduces three “dummy” blocks for each player, these can be moved like normal Corps but if they are ever in the same space as an enemy block they are automatically eliminated. These rules also allow for a certain amount of free deployment of your blocks. It seems weird to me that these rules are labeled “Grognard” as all but the free deployment are pretty straightforward, especially if you’ve played any block games before (and block games are far from the complex end of wargaming). I would probably recommend the Grognard variant for anyone trying the game out, although maybe use the historical set up for a first game instead of the free deployment.

Game end. Napoleon succeeded in seizing Erfurt but ran out of steam before he could eliminate the final Prussian Corps in the region. Meanwhile the French attack in Leipzig was unsuccessful. The Prussians survive and claim victory!

Overall, I enjoyed playing Napoleon 1806 but I don’t think I will be seeking out more games of it in the immediate future. I am, however, very interested in trying more games in the series. My main objection to Napoleon 1806 is the asymmetry of the game. The Prussians are much weaker than the French and are largely playing a game of delay and harass rather that meeting the French on equal terms in the battlefield. In a big punch up fight, more often than not the French will win. I don’t think this is a flaw in the game and in fact from my limited understanding of the Napoleonic Wars this feels like a good representation of the history. I just didn’t find the Prussians to be very fun to play - and that is entirely down to what I like to get out of my gaming experience. My favourite of the Columbia Block games I’ve played is Richard III which is arguably the one closest to a big dumb fight where you smash your armies together in horrifically bloody outcomes. The delaying tactics of the Prussians while interesting where not the kind of experience I want out of my block games. This is compounded by the knowledge that if I kept playing it every time I taught someone Napoleon 1806 I would have to play the Prussians because with a new player the chances of me just crushing them as Napoleon and giving them a bad impression of the game are far too high. I think when you learn the game Napoleon is highly favoured to win, but as you play more I suspect the balance evens out considerably. I know that there are people out there who really enjoy playing the Prussians in this game so for lots of people the asymmetry will absolutely work but for matters entirely relating to personal taste I don’t think it’s for me. I am interested in trying Napoleon 1807, though, as I do like most of the features of this system and I suspect it could produce a game I truly love.