Apparently I’m closing out this year by playing block games from French publishers. I’m okay with that honestly. I first became aware of This War Without an Enemy via a Teach and Play video on the Homo Ludens YouTube channel. In a rare turn of events for me, I almost immediately bought the game even though I had no idea when I would get it to the table. That was some months ago but thanks to a new acquaintance from the next county over, I was able to finally play it! Where Napoleon 1806 was interesting because it offered a distinct departure from the block games I was used to, This War Without an Enemy is interesting because it is something of a development of the Columbia block games system that I already like. This War Without an Enemy actually began its life as a game intended for Columbia but when it moved to Nuts! Publishing it expanded in complexity and I was very interested to see what that complexity brought to a classic block formula that I’ve spent many hours enjoying already.

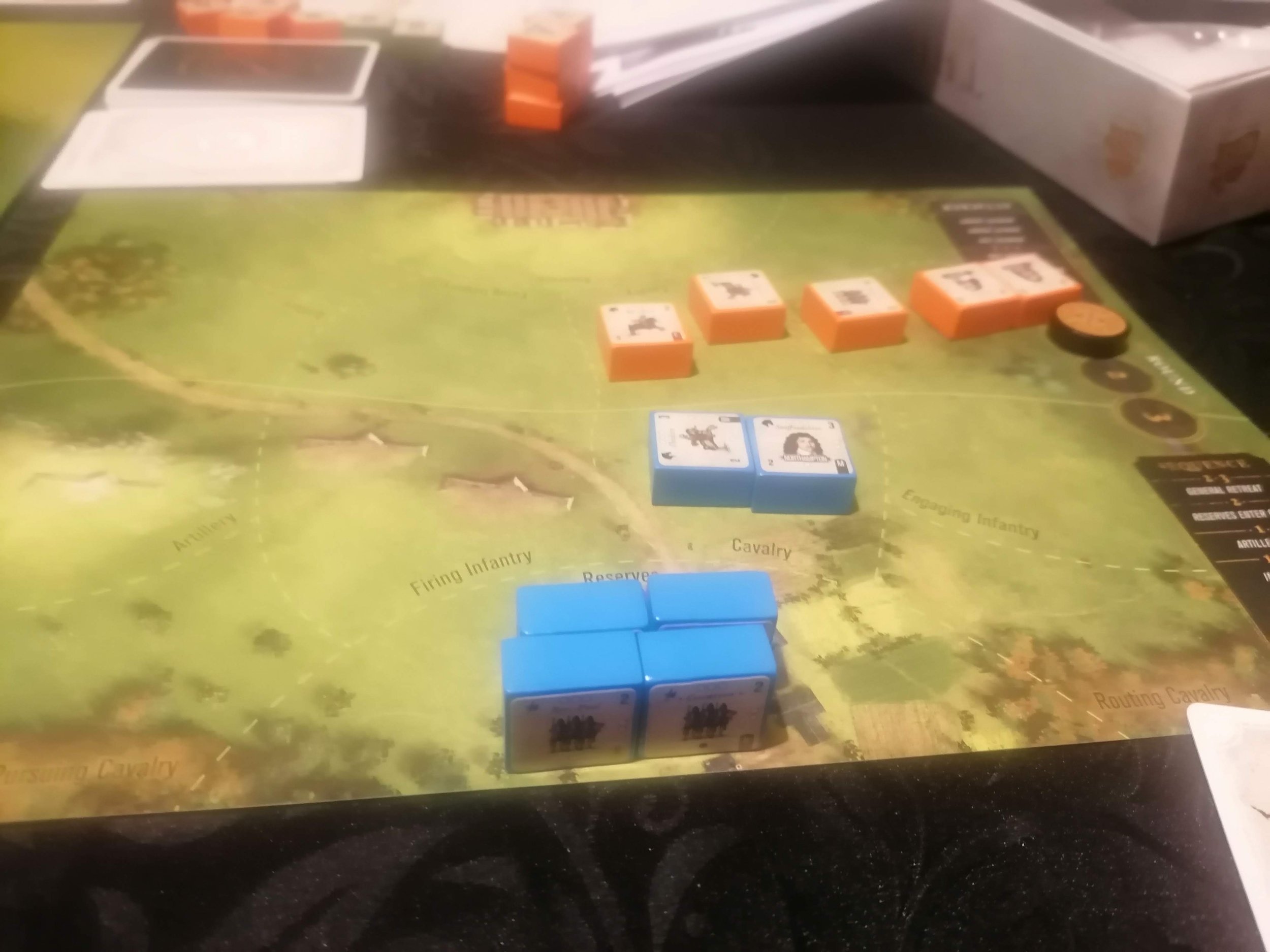

We played the mid-length scenario which begins in 1644. This is the set up - I ended up taking the Royalists side and I have to say those blocks up in Scotland were quite scary. Also, apologies for the glaring light - we played on my kitchen table and the light is a bit much..

I have to confess that I don’t know very much about the English Civil Wars. I know the gist of it - parliamentary revolt, fighting with the royalist faction, Charles I beheaded, Oliver Cromwell, etc. - but I would not claim any in depth understanding of the conflict or its major elements. Similarly, I recognise terms like New Model Army but it has been many years since I had them explained to me and that was at a very basic level. This all means that I don’t really feel qualified to comment upon This War Without an Enemy as a historical simulation. The game simulates the First English Civil War from 1642-1646, although for our first game we only played the mid-length scenario which begins at the start of 1644. The game is played across a number of years. Each year, except 1642, consists of six turns - five normal turns and one winter turn. At the start of a year players are dealt a hand of six card from their separate decks. The decks will change over the course of the game as different cards enter or leave the deck based on the current year but you won’t see every card in a given play. Each turn begins with both players simultaneously picking a card. Whoever plays the higher value card gets to pick who goes first. The first player will do all of their movements, recruitment, etc. and then the second player, after which all the battles will be resolved, supply will be checked, sieges will progress, and the next turn begins. Most cards also have an event on them and when played the event will trigger and the player will get the card’s value, you don’t choose between the two.

The game opened with a Parliamentarian attack that pushed me out of Oxford and put the king’s life in danger. A subsequent siege quickly saw capture of the town as well. Meanwhile I laid siege to Hull and Plymouth but with my artillery in the routed army of Oxford I couldn’t effectively storm either.

The first obvious addition to the complexity of the Columbia system, besides the changing decks and more complex cards, is in the actions that can be taken. It’s not that This War Without an Enemy introduces a ton of new actions, most of the choices have been available in some form in Columbia games I’d played before, but by offering all of them it stands somewhat apart. In addition to activating an area’s blocks and moving them you can spend actions on your turn to reinforce blocks - adding new blocks to the board or increasing steps of existing blocks with some limitations (i.e. artillery usually cannot be increased) - or to conduct a muster, pulling blocks from adjacent regions into one central point. Again, none of these are strictly revolutionary - muster existed in Crusader Rex and as an event in Richard III, and reinforcement is similar to how it worked in Julius Caesar. Having both in the one game adds a bit more complexity, and there are more options to weigh for each of them with restrictions.

I succeeded in forcing both Hull and Plymouth to surrender, which kept me in the game in terms of victory points, but I’ve lost Chester and armies are massing to deliver a series of punishing blows to my remaining forces .

The real complexity ramps up when you get into the combat. This War Without an Enemy has three unit types: infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Combat is now resolved on a separate battle board which functions more like a player aid to help you track the relevant phases. Instead of units have letter ratings determining their attack order, the order is based on their type. Artillery shoots first, but only contributes to the first round, while infantry can shoot before the cavalry attack but at a penalty or they can engage after the cavalry at their full effectiveness. Deciding when to shoot or engage with your infantry remains interesting, especially as the Defender must decide first for all their blocks before the attacker does. There are further complexities, such as if one side’s cavalry successfully defeats the other side there’s a chance they will pursue the fleeing troops and leave the battle entirely - which can be a disastrous result.

While combat order is very different in This War Without an Enemy, dealing hits will be instantly familiar to people who know Columbia’s system. You roll dice equal to your strength and try to roll under your effectiveness to deal hits. This adds a nice level of familiarity to balance out the new complexity of the battle order. It is not entirely without further elements to consider though as there are more modifiers than I’m used to in Columbia games. Artillery shoots at cavalry with a penalty while cavalry attacks infantry at a bonus, for example, so you have to factor that into your combat decisions as well.

The battle map - this was actually a relatively small battle in this game. The standing blocks are in reserve and only show up in the second round, which would go very badly for me as good dice meant that my opponent eliminated my cavalry and my reserves had to engage as the attackers and battle second.

The battles can also be enormous. While there are border limits in place on the map, many regions have open borders that let you move any number of blocks across them. This allows for some truly epic battles, which are also immensely risky if you happen to be on the losing side. The first turn of my game featured probably the largest battle I’ve experienced in a block game. I really enjoyed it because with the new combat system there are interesting decisions to be made each round, but also it seemed a bit like a tactical error to actually fight this battle - especially since I lost. While I really enjoyed the system in the larger battles, for smaller ones it can be a bit of a chore to set everything up. It feels like the system could have benefited from some skirmish rules for when battles are below a certain block count. Going through all the motions for a 3v1 battle felt a bit like overkill. But then again there are quite a few rules in This War Without an Enemy so maybe more rules could be too much.

I make a brief, and ill-fated, attempt to launch an attack in Oxford before the two Parliamentarian armies can converge on me at Bristol. Meanwhile the Parliamentarians push into north Wales to crush my remaining troops there before they can effectively counterattack and the siege of Hull continues.

One other change I really like in This War Without an Enemy’s combat is how it handles retreats. Instead of withdrawing each block on its own, the only option for a retreat during combat (ignoring the potential withdraw before combat) is to order a general retreat. This triggers one final round of combat where both sides fight at a significant penalty, worse for the retreating side, and ends the combat at the end of that round. This feels much more appropriate for how warfare would have been fought, you couldn’t just surgically remove one section of your army from a fight, and creates a tense series of decisions around how long do you stay in the fight. It actually kind of reminded me of combat in the Levy and Campaign system, where knowing how long to stay in a fight is a crucial decision as well.

Things are looking bad for poor King Charles hiding out in Plymouth. My attack in Oxford failed and the remnants were eliminated in Bristol. The Welsh battle was less decisive but still forced me further into the mountains. Meanwhile the siege of Hull drags on but is not looking good for me.

This War Without an Enemy also adds quite a complex set of rules around the resolving of sieges - and based on my experience you will be doing quite a few sieges in this game. Controlling cities is key to gaining victory points, so taking cities is in many ways more important than winning field battles. Sieges include rules for using artillery to create breaches in the city’s walls which can set you up for a much easier time if you choose to storm the city. Alternatively, you can choose to just wait out the siege, slowly ratcheting up the pressure until the defenders surrender. There are also rules for sortieing out from the city and for sending a relief army, although neither came up in my game.

When reading the rules I thought the siege system might end up being too complex and not interesting enough to warrant that complexity, but in play I found it much easier to manage than I expected and really enjoyable. This is definitely the best set of siege rules I’ve found in a block game yet. There are probably still a few places that it could be slightly simpler without losing what makes it great - like does London and only London really need an exception where enemy artillery can block a naval move to/from it when it’s under siege? - but overall it’s really good and probably one of the highlights of the game for me.

The end game state - Charles found his spine at the last minute and drove off several attempted storms of Plymouth but Hull eventually surrendered giving the Parliamentarians the final VP they needed to win after only two years of campaigning.

If I have one critique of the game it is that it feels a little too complicated for what it is. It’s not the big picture complexity that’s the problem, but rather all the little bits of chrome here and there you have to keep track of. I know there are systems that we completely forgot about during our game because there’s just so much to take in on a first game. This is a game where you read the rules, play it once, and then read the rules again to see what you missed. It’s not that the game is too complex to play easily, but I do kind of wonder if it wouldn’t be a little bit better if the rules were pared down slightly to keep some of that simplicity that the Columbia block system offers. There are lots of rules I didn’t mention in this post, some of which, like the unit regionalisation, I actually quite like but at the same time there were a few rules I came across when learning the game where I felt like “is this really necessary?” The game is also fairly long and the time spent with my nose in the manual checking a rule just extended the play time further. I could feel us speeding up as we played so I bet if you got it to the table regularly you could play it in a few hours, but as you’re learning it I think the full campaign is probably more of an all afternoon play experience.

Overall it’s a pretty minor nitpick, and I don’t think it should dissuade anyone from trying This War Without an Enemy. It’s a really interesting design and a game I hope to play again soon while the mechanisms are still fresh in my mind. I don’t know if it is going to be a regular feature of my gaming life for many years to come, but it’s an interesting development of a series I already liked and I’m excited to explore it more. I also think it shows that the core of the Columbia block system is ripe for expansion and revision to make games that are both similar and still very distinct. I would be very interested in seeing more games like This War Without an Enemy that take that core system and adapt it in new ways.